Gay Marriage Turns 10

The Supreme Court decided Obergefell v. Hodges ten years ago today, June 26, 2025. The case legalized gay marriage nationwide by determining that state marriage licensing laws that restrict licenses to heterosexual couples violate same-sex couples’ constitutional right to marry under the 14th Amendment.

With the stroke of pen, five unelected justices, in a hotly contested case, created a constitutional right to marriage that didn’t exist prior to June 26, 2015. The justices simply substituted their peferences for what the Constitution should say, for what the Constitution does say, or more importantly, doesn’t say.

Normative issues aside, this is the primary reason Obergefell is Constitutional garbage. It makes a mockery of both the 10th and 14th Amendments of the Constitution and elevates the Supreme Court to a super-legislature without oversight or accountability. If you have to bend the rules to win, then there’s something amiss.

A Right to Marriage?

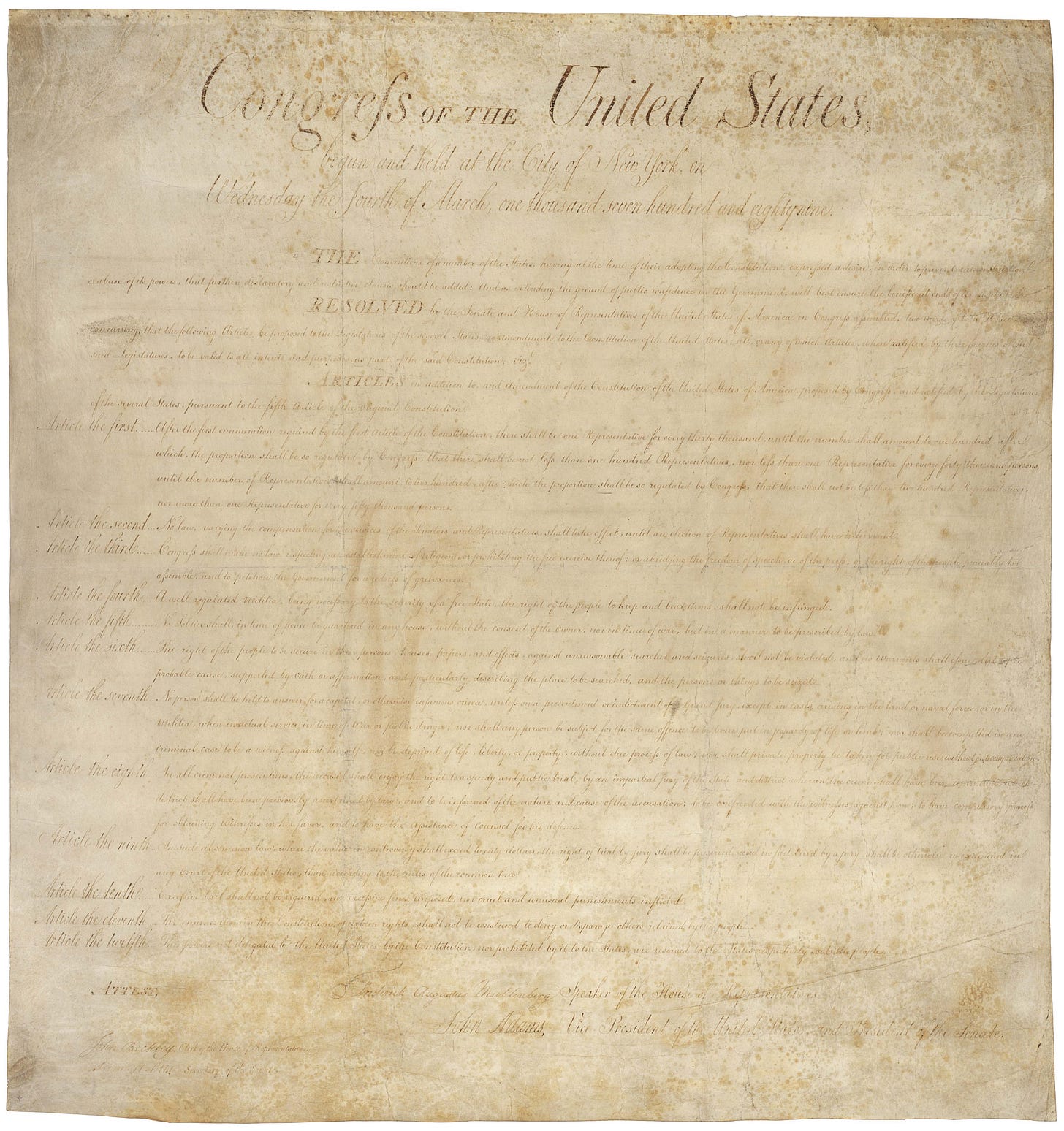

The United States Constitution does not provide anyone, of any gender, a Constitutional right to marriage. Like abortion, the Constitution is silent on the issue. Per the 10th Amendment, if the Constitution is silent on a matter, then the federal government doesn’t have the power to regulate it. This should be the end of inquiry, period, full stop.

10th Amendment: The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

Per the Constitution, marriage can only be regulated by the states. Federal judges have no jurisdiction, or authority, to opine on state laws except in limited circumstances. But that hasn’t stopped them from doing so, and with increased frequency. When federal judges, particularly Supreme Court justices, overstep their prescribed authority and opine on matters over which they have no Constitutional power, they’re not only way out of bounds, but are actively violating the principles of federalism upon which our government was built.

On Federalism

Federalism is a way of governing that divides powers between a central, or federal, government, and smaller constituent regional governments, with both deriving their powers from a single constitution. In the United States, the smaller regional governments are state governments.

The nature and scope of the division of powers between the federal and state governments is clearly outlined in the U.S. Constitution. Should the people want to change this framework in any way, the Constitution provides a clear process for amendment.

U.S. Constitution, Article V: The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments, which, in either Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress; Provided that no Amendment which may be made prior to the Year One thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any Manner affect the first and fourth Clauses in the Ninth Section of the first Article; and that no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate.

Note the players involved in the amendment process: Congress and the states. Neither the executive nor judical branches are among them. For judges to take it upon themselves to reinterpret the Constitution so it speaks on matters about which it is silent is about as unconstitutional as you can get.

The Role of the Supreme Court

The job of the Supreme Court is to determine the Constitutionality of laws, not to create new Constitutional rights.

The Constitution is six pages long, but it took the Roe court 65 pages to create a constitutional right to an abortion, an issue upon which the Constitution is silent. A 6th grader can read the Constitution and determine that it doesn’t mention abortion, anywhere.

In 1982, nine years after Roe, the high court ruled in Phyler v. Doe that illegal aliens have a constitutional right to receive a free K-12 public education, even though the Constitution is silent on the matter as well. I think they accomplished their mission in about 28 pages.

Fast forward to June 26, 2015 and SCOTUS was at it again, but this time they created a new constitutional right to marriage, including same-sex marriage, another issue about which the Consitution has nothing to say. Same 6th grader can read and read but marriage isn’t mentioned anywhere. This new right articluated in Obergefell v. Hodges simply has no basis in the Constitution. I don’t remember how many pages the Obergefell opinion is (absent dissents), but it’s a lot more than six.

The normative arguments about these underlying issues, which are almost always flashpoints, aren’t for courts to engage. They’re reserved for the democratic process and the ballot box. The courts’ job isn’t to substitute its own opinions about the Constitution for what the Constitution actually says, or doesn’t say. Their job is to look at the document and apply the principles of statutory interpretation in order to ascertain the text’s meaning on a particular topic.

When courts discard their interpretive mandate and substitute their preferential meaning of words for the actual meaning of words, chaos always ensues. This is the heart of the debate over originalism versus textualism versus pragmatism (living Constitutionalism), etc.

SIDEBAR » Statutory interpretation is the process by which judges interpret and apply laws to specific situations since no legislation can address every possible scenario it’s intended to address, especially as unforseen circumstances arise from technological developments or similar types of shifts.

A court’s goal is always to determine what the words in the relevant statute, law, or legislation (all the same thing) mean or are trying to communicate so it can be properly and faithfully applied to the situation at hand. Naturally, meanings of words change over time, so it’s important for courts to discern the meaning of words at the time they were written and adopted, not necessarily as we understand them today. Similarly, if words don’t actually appear in the particular statute, then there’s nothing to interpret.

In statutory interpretation, there are textual canons, or rules of thumb, that must be followed for understanding the words of a particular text. These include plain meaning, technical meaning, rules against surplusage, etc. These also include not reading words into a law that simply aren’t there.

Back to the Constitution

The 10th Amendment, the last amendment in the Bill of Rights, gives people and states countless rights that aren’t delegated to the federal government for regulation. Marriage is among them. It is for the people, not the courts, to decide who should have the right to receive both the benefits and burdens of a marriage license, which is issued by the states, not the federal government.

For the Supreme Court to create a Constitutional right to marriage runs roughshod over every American’s 10th Amendment right to decide who can be part of the institution of marriage and who cannot. The Court effectively bypasses the democratic process and announces a new mandate it has neither the Constitutional power nor authority to issue. It’s perceived power in this area comes only from itself.

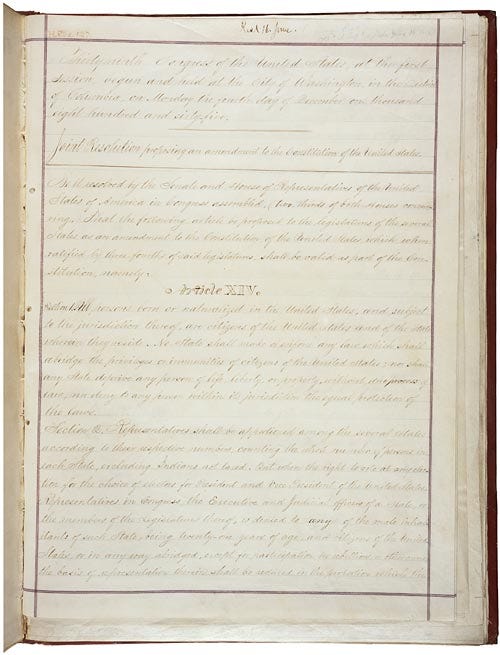

Moreoever, to find that 147 years after its ratification, the liberty component of the 14th Amendment’s due process clause does, after all, provide Americans with a Constitutional right to certain types of marriages, was breathtaking. And realizing that the next clause guaranteeing equal protection of the laws doesn’t actually mean that the law is applied evenly, but that everyone has an affirmative right to an equal outcome under that, and every other law, was really mindblowing.

14th Amendment, Section 1:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States;

nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law;

nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Those who view the 14th Amendment in this expansive way are essentially claiming that as social mores and values change, so too does the Constitution’s grant of rights. When the high court adopts this position, it’s a judicial fraud not just on the Constitution, but also on the entire country and the democratic process. Sometimes our side wins, sometimes it loses, but that’s the nature of self-government. Participation is what makes the wheels go round, not judicial decrees from a bench.

How Did We Get Here?

Long before Obergefell, there was Goodridge (2003), and before Goodridge, there was Windsor (2013). But for these cases, there would not, and could not, have been an Obergefell.

Let’s start in Boston in November 2003.

The Supreme Judicial Court, via its Chief Justice Marsha Marshall, issued an opinion Goodridge v. Dept. of Public Health and that said denying marriage licenses to same-sex couples violated Massachussetts law and the Massachusetts Constitution, specifically its due process and equal protection clauses. Since marriage is properly a state issue, there is nothing Constitutionally offensive per se about this decision. The offense comes from its methodological bravado.

In order to arrive at its conclusion, the Massachusetts court had to do quite a bit of legal jujitsu as one can only be denied due process or equal protection of the laws if the specific law at issue actually applies to the one asserting a denial of rights. For example, laws that regulate child labor don’t apply to adult labor. Hence, an adult cannot claim that a child labor law violates his or her constitutional rights. Pretty straightforward, right?

Since the primary purpose of marriage is procreation (as stated in numerous judicial opinions across the country), and gay couples can’t procreate, marriage laws didn’t apply to homosexual partnerships, any more than social security laws apply to minors. Pretty straightforward, right?

Marriage is the bedrock of the nuclear family and the nuclear family is the foundation of human societies, so the fact that marriage only involves heterosexual couples is nothing new. Indeed, marriage and family are so important to a stable society that governments worldwide have sought to promote and protect them for millenia. To say that marriage as an institution isn’t for straight couples is both dishonest and a category mistake.

SIDEBAR » Category mistakes, or errors, happen when things belonging in one particular category are presented as actually belonging to a different category. For example, if a guy is holding a frog and tells you he’s actually holdig a bird, he’s making a category mistake. When my dad told me to use elbow grease when I cleaned the bathroom, and I went to the garage to look for it, I was making a category mistake. Saying that transgender women are women is a category mistake. Saying that two men or two women can create a marriage is a category mistake.

To cure a category mistake, one must simply recognize their error and withdraw their claim. Alternatively, some bypass the self-own and move to demolish the category altogether, then recasting it into something totally different. Categories are nothing more than social constructions, right? While this “demolition and transformation” can be successfully undertaken with clever wordplay, it doesn’t actually demolish or transform reality. It doesn’t change what’s real into something unreal. And, that’s the rub—at some point it catches up to you.

In Goodridge, the court didn’t just make a category mistake, it sought to demolish the entire legal category of marriage. In her opinion, Justice Marshall disregarded the reality that marriage is a pre-political human institution that recognized and protected by the state, in favor of a new definition asserting that marriage is actually created by the welfare state and carries with it a “cornucopia of substantial benefits.” Marshall didn’t engage the anthropological question of what marriage actually is, instead she made the issue one of equal access to the state’s “cornucopia of substantial benefits.” Rather than a natural ordering of human life, marriage would now be reduced to a contractual arrangement between two consenting adults, of either sex, and the state.

Obviously, deciding that marriage isn’t anterior to the state, but a creation of the state didn’t actually change the nature of the institution but it dramaticallty changed the legal framework under which it would be regulated.

Goodridge was the first domino to fall in the fight for gay marriage, which incidentally wasn’t initially high on the gay rights movement’s list of priorities. But once it was, it was pursued earnestly and strategically.

With this legal victory in hand, the next goal was to have each state follow Massachusetts and amend their marriage licensing laws to align with this new characterization of marriage. Once all 50 states fell in line, gay marriage would be a legal reality nationwide. But democracy is hard work and changing hearts and minds is tough, especially when you’re trying to convince people that somehow they all missed the boat in realizing that marriage wasn’t really a gendered insitution after all.

There had to be another way.

—

Back next time with the case that katapulted gay marriage into the national spotlight and laid the groundwork for Obergefell: U.S. v. Windsor.

xo,

Kelley

June 26, 2025