What is Pride Month, and When Did It Begin?

If you read my content on The Savvy Citizen, you know I’m a big fan of the Congressional Research Service (CRS). It’s staff researches the full range of topics that tend to show up on Congress’ radar, and works closely with the Members, their advisors, and congressional committees to ensure they have all of the information they need when drafting legislation. Most of their reports are public and easy to review online. I highly recommend it!

I can certainly give you a description of Pride Month and explain its origins, but since the federal government has already done a pretty thorough job, I think it makes perfect sense to share their content without my commentary, for now.

Congressional Research Service Publishes Report on LGBTQ Month

During the Biden administration, the CRS researched for the first time what is now called LGBTQ Pride Month in the United States and then published a report providing a summary of its history, purpose, and supporting government actions. The report, which was published on October 17, 2022, hasn’t been updated so it doesn’t account for the second half of Biden’s term or Trump’s second term. Bear this in mind when you read the report which is reproduced in full below.

But first, a sidebar!

SIDEBAR » As you read the report, consider the following questions:

(1) What exactly is Pride Month and what exactly is it celebrating?

(2) Why does the federal government direct public resources, aka taxpayer money, to Pride Month?

(3) When and why did Pride Month transform from local parades across the country celebrating gay liberation from social shame to a national observance, acceptance, and even Congressional and Presidential affirmation not just of homosexuality, but also of bisexuality, transgenderism, intersexism, and an infinite number of queer and gender-queer identities?

Here’s the text of the CRS report.

Introduction

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ) Pride Month, which is observed during the month of June, celebrates the achievements of the LGBTQ community and recognizes the historical and cultural contributions made by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer individuals.

This guide is designed to assist congressional offices with their work related to LGBTQ Pride Month. Resources include census and demographic data, CRS reports, presidential proclamations, and cultural and historical resources.

Background and History

LGBTQ Pride Month is observed throughout the month of June to commemorate the Stonewall Uprising, a landmark moment in LGBTQ history. On June 28, 1969, patrons of The Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Manhattan, resisted a police raid, igniting demonstrations and protests that sparked the modern gay rights movement.1

Pride Month was first formally recognized on June 11, 1999, when President William J. Clinton issued Proclamation 7203, recognizing June as "Gay and Lesbian Pride Month."2 On June 1, 2009, President Barack H. Obama expanded the commemorative month to include bisexual and transgender Americans when he declared June "Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride Month."3 On June 24, 2016, President Obama designated Stonewall National Monument, America's first national park site dedicated to LGBTQ history.4

Today, LGBTQ Pride Month celebrations commonly include parades, marches, parties, concerts, and events across the nation.5 LGBTQ rainbow pride flags are also displayed prominently throughout the month. Gilbert Baker, an Army veteran, artist, and gay rights activist, created the rainbow flag in 1978 as a symbol of the diversity of the community.6

Legislation

The House and Senate have passed multiple resolutions recognizing LGBTQ Pride Month over the years:

H.Res. 1198 (2022), Encouraging the celebration of the month of June as "LGBTQIA+ Pride Month."

S.Res. 652 (2022), A resolution recognizing June 2022 as "LGBTQ Pride Month."

H.Res. 489 (2021), Encouraging the celebration of June as "LGBTQIA+ Pride Month."

S.Res. 261 (2021), A resolution recognizing June 2021 as "LGBTQ Pride Month."

H.Res. 1014 (2020), Encouraging the celebration of June as "LGBTQ Pride Month."

S.Res. 627 (2020), A resolution recognizing June 2020 as "LGBTQ Pride Month."

Sample Congressional Speeches and Recognitions

Some Members of Congress typically make floor statements, issue press releases, or enter Extensions of Remarks into the Congressional Record to recognize federal holidays and observances. The following are some recent LGBTQ Pride Month examples:

Representative Danny K. Davis, "In Celebration of June as National Pride Month," Congressional Record, daily edition, vol.168 (June 28, 2022), p. E676.

Representative Robin Kelly, "Fighting for the Rights of LGBTQ+ People," Congressional Record, daily edition, vol.168 (June 22, 2022), p. E676.

Representative Sanford D. Bishop Jr., "Commemorating LGBTQ Pride Month," Congressional Record, daily edition, vol.167 (June 22, 2021), p. E676.

Senator Patty Murray, "Pride Month," Congressional Record, daily edition, vol.166 (June 30, 2020), p. S4028.

Representative Brian Fitzpatrick, "Fitzpatrick Recognizes LGBT Pride Month," press release, June 5, 2018.

Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, "LGBT Pride Month," Congressional Record, daily edition, vol.163 (June 12, 2017), p. H4836.

Presidential Proclamations and Remarks

One of the many uses of a presidential proclamation is to ceremoniously honor a group or call attention to specific issues or events. Some recent statements commemorating LGBTQ Pride Month from the Compilation of Presidential Documents are the following:

Presidential Proclamations—Joseph R. Biden, Jr. (2021-)

Presidential Proclamations—Donald J. Trump (2017-2021)

Presidential Proclamations—Barack H. Obama (2010-2017)

Presidential Proclamations—William J. Clinton (1994-2001)

Statistics

Numerous federal and private sources maintain statistics on the LGBTQ population. Some useful data include the following:

The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law, "LGBT FAQs."

U.S. Census Bureau, "LGBTQIA+ Pride Month: June 2022." Stats for Stories, June 2022.

Jeffrey M. Jones, "LGBT Identification in U.S. Ticks Up to 7.1%." Gallup, Inc., February 22, 2022.

Historical and Cultural Resources

Numerous organizations provide information on the history and culture of LGBTQ Americans. Some of these include the following:

National Archives, LGBTQ Pride Month. The National Archives is home to a vast collection of documents from the U.S. government on issues of sexual identity and rights.

Library of Congress; Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Pride Month. In recognition of LGBTQ Pride Month, the Library of Congress has created a site that highlights events, exhibits, collections, and educational materials related to LGBTQ Pride Month.

LGBTQ History in Government Documents. This guide highlights primary sources documenting the U.S. federal government's stance on issues related to the LGBT movement from the 1800s to the present day.

National Park Service, Stonewall National Monument. The National Park Service features historic properties listed in the National Register and National Park units "highlighting important aspects of the LGBTQ experience in America."

Related CRS Reports

CRS Report R43539, Commemorations in Congress: Options for Honoring Individuals, Groups, and Events, coordinated by Jacob R. Straus. This report provides a discussion of the legislative and nonlegislative commemorative options available to Congress.

CRS Report R44431, Commemorative Days, Weeks, and Months: Background and Current Practice, by Jacob R. Straus and Jared C. Nagel. This report provides information on commemorative legislation that recognizes a specific time period and discusses options for Congress.

*End of Report*

The Library of Congress Publishes Resources on LBGTQ Pride Month Too

The Library of Congress (LOC) also maintains content celebrating Pride Month too. Their content is available to the public and more comprehensive than the CRS report, which has a specific audience. You can find their resources here.

Here’s the text from their Welcome page.

Welcome from the Library of Congress

June is Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ) Pride Month. This month-long celebration demonstrates how LGBTQ Americans have strengthened our country, by using their talent and creativity to help create awareness and goodwill. The first Pride March in New York City was held on June 28, 1970, on the one year anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. More

The legacy of LGBTQ individuals is being discovered by interested readers and seasoned researchers perusing unparalleled global collections. The acquisition of historic material and the ongoing program of copyright deposits will continue to enrich the Library’s holdings of LGBTQ materials.

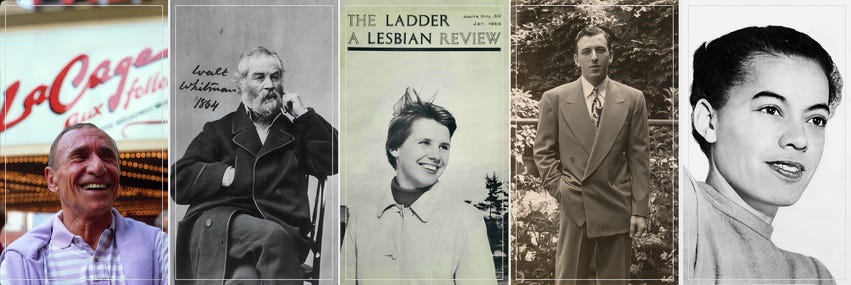

The collections of the Library of Congress contain many books, posters, sound recordings, manuscripts and other material produced by, about and for the LGBTQ community. The contributions of this community are preserved as part of our nation’s history, and include noted artistic works, musical compositions and contemporary novels. The Library’s American collections range from the iconic poetry of Walt Whitman through the manuscripts of the founder of LGBTQ activism in Washington, D.C., Frank Kameny.

The Library of Congress is the largest single repository of world knowledge in a single place. In addition to having the mission of acquiring and preserving this exponentially growing body of knowledge, the Library is responsible for making all of its vast collection accessible to all.

And here’s the text from their About [Pride Month] page:

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ) Pride Month is currently celebrated each year in the month of June to honor the 1969 Stonewall Uprising in Manhattan.

The Stonewall Uprising was a tipping point for the Gay Liberation Movement in the United States. In the United States the last Sunday in June was initially celebrated as "Gay Pride Day," but the actual day was flexible. In major cities across the nation the "day" soon grew to encompass a month-long series of events.

Today, celebrations include pride parades, picnics, parties, workshops, symposia and concerts, and LGBTQ Pride Month events attract millions of participants around the world. Memorials are held during this month for those members of the community who have been lost to hate crimes or HIV/AIDS.

The purpose of the commemorative month is to recognize the impact that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender individuals have had on history locally, nationally, and internationally.

In 1994, a coalition of education-based organizations in the United States designated October as LGBT History Month. In 1995, a resolution passed by the General Assembly of the National Education Association included LGBT History Month within a list of commemorative months. National Coming Out Day (October 11), as well as the first "March on Washington" in 1979, are commemorated in the LGBTQ community during LGBT History Month.

Annual LGBTQ+ Pride Traditions

The first Pride march in New York City was held on June 28, 1970, on the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. Primary sources available at the Library of Congress provide detailed information about how this first Pride march was planned and the reasons why activists felt so strongly that it should exist.

Looking through the Lili Vincenz and Frank Kameny Papers in the Library’s Manuscript Division, researchers can find planning documents, correspondence, flyers, ephemera and more from the first Pride marches in 1970.

This, the first U.S. Gay Pride Week and March, was meant to give the community a chance to gather together to "...commemorate the Christopher Street Uprisings of last summer in which thousands of homosexuals went to the streets to demonstrate against centuries of abuse ... from government hostility to employment and housing discrimination, Mafia control of Gay bars, and anti-Homosexual laws" (Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee Fliers, Franklin Kameny Papers).

The concept behind the initial Pride march came from members of the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations (ERCHO), who had been organizing an annual July 4th demonstration (1965-1969) known as the "Reminder Day Pickets," at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. At the ERCHO Conference in November 1969, the 13 homophile organizations in attendance voted to pass a resolution to organize a national annual demonstration, to be called Christopher Street Liberation Day.

As members of the Mattachine Society of Washington, Frank Kameny and Lilli Vincenz participated in the discussion, planning, and promotion of the first Pride along with activists in New York City and other homophile groups belonging to ERCHO.

By all estimates, there were three to five thousand marchers at the inaugural Pride in New York City, and today marchers in New York City number in the millions. Since 1970, LGBTQ+ people have continued to gather together in June to march with Pride and demonstrate for equal rights.

Watch documentary footage of the first Pride march, "Gay and Proud," a documentary by activist Lilli Vincenz: [Use the QR code below to watch the video.]

Executive and Legislative Documents

The Law Library of Congress has compiled guides to commemorative observations, including a comprehensive inventory of the Public Laws, Presidential Proclamations and congressional resolutions related to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual Transgender and Queer Pride Month.

This section of the LOC’s website also includes links to LOC Resources, including events, blogs, social media, research guides, and links to all of their collections in the arts, sciences, literature and poetry. The available information is voluminous.

The National Archives Maintains Pride Month Content Too

The National Archives and Records Administration maintains records on LGBTQIA+ records as well. You can access those records on the“LGBTQIA+ Issues in Records at the National Archives” section of their website here. They describe their holdings as “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Pansexual, Transgender, Genderqueer, Queer, Questioning, Intersex, Agender, Asexual, Ally, and other queer-identifying community records.”

SIDEBAR » You’ll notice I’ve used several different versions of the LGBTQ acronym. I’m simply using exactly what each government agency uses even though its inconsistent. So, if you’re part of the alphabet police, I’m innocent.

—

Test Your Knowledge

I’ve posted Pride Month content from three federal government resources: the Congressional Research Service, the Library of Congress, and the National Archives. This simply scratches the surface, but my post can only be so long.

While Pride Month is a cultural phenomenon, it’s also a celebration of the successful conclusion of the gay rights movement. By 2020, they achieved every social and legal milestone sought, and more. Most reasonably educated gay and part-time gay (bisexual) people agree.

So, why are we still litigating these issues? Hint: Think T, Q, I, A, + …

I’ll be back in my next post unpacking the legal evolution of “pride” writ large, much of which is scattered throughout the content above, including Presidential Proclamations, Public Laws, and Congressional Resolutions. After that … we go to court.

—

I’ll wrap with a “knowledge test.” Having read the text above, can you answer the questions I posed at the beginning? Let me know in the comments!

(1) What exactly is Pride Month and what exactly is it celebrating?

(2) Why does the federal government direct public resources, aka taxpayer money, to Pride Month?

(3) When and why did Pride Month transform from local parades across the country celebrating gay liberation from social shame to a national observance, acceptance, and even Congressional and Presidential affirmation not just of homosexuality, but also of bisexuality, transgenderism, intersexism, and an infinite number of queer and gender-queer identities?

—

Back ASAP!

xo,

Kelley

June 19, 2025

Well researched and documented! Nice job.